Condé Nast has released the June 2009 edition of Architectural Digest Magazine! Featured articles include a taste of english country style in the Smoky Mountains, easing a historic farm into the present is a labor of love, in the heart of napa valley, a contemporary farmhouse settles in, creating a stylish throwback to the 1970s, and soaring volumes in the country allow a family to reach out and connect.

Condé Nast has released the June 2009 edition of Architectural Digest Magazine! Featured articles include a taste of english country style in the Smoky Mountains, easing a historic farm into the present is a labor of love, in the heart of napa valley, a contemporary farmhouse settles in, creating a stylish throwback to the 1970s, and soaring volumes in the country allow a family to reach out and connect.

Tale of Toad Hall

A Taste of English Country Style in the Smoky Mountains

A profound love of the land, mixed with a lifelong passion for home entertaining, is the driving force behind the imposing collection of five log structures that Kreis and Sandy Beall have built on a picturesque 32-acre site in Tennessee’s Great Smoky Mountains. With southern understatement, the Bealls and their Atlanta-based interior designer, Suzanne Kasler, refer to the compound’s 12,000 square feet of buildings, including the princely main house, as “log cabins,” much in the way that southerners might self-deprecatingly refer to the majestic two-story columns of their plantation houses as “sticks.”

The logs in question are more than amply proportioned antique timbers collected, as Kreis Beall explains, “by a man in Knoxville, Tennessee, with a passion for finding and gathering timbers from old log barns.” If they form a robust and richly textured background for the Bealls’ vast collections of 18th- and early-19th-century European furnishings and household ornaments, as they do, they also adamantly refuse to remain in the background. Joined by rugged boulder chimney breasts, the logs set the tone for the interiors’ unshakable and comforting stability.

Back to Basics

Easing a Historic Farm into the Present is a Labor of Love

Certain houses have to wait longer than others to find the right people to bring them back to life.

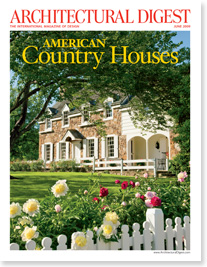

In 1935 the Colonial Revival architect Richardson Brognard Okie built one of his classic Pennsylvania farmhouses for a Philadelphia investment counselor named Robert Boltz. The client purchased 340 acres and commissioned Okie to design a working dairy farm, complete with a main residence, five outbuildings and a man-made lake and water raceways that ran an actual waterwheel. Drawing on both American and English vernacular styles, as was his habit, Okie gave his client one of his beautifully detailed design pastiches: The main house was made of stone and featured such trademark Okie gestures as a recessed porch with double arches, a chunky pediment over the front door, dormer windows on the second floor that are inset through the cornice, set-back wings with different rooflines, lanterns on shelf brackets, and custom hardware in a range of designs.

Neither the client nor his architect was playing farm, however. The basement of the main house, which is lined from floor to ceiling in white subway tile, featured built-in tubs piped with cold well water in which milk cans were kept until they were picked up for distribution. There was a bank barn for milking the cows; a large L-shaped building containing work spaces and implement sheds; and a blacksmith’s shop, where all of the property’s hardware was hand-forged following Okie’s drawings. There was a double-sided corncrib, which was converted into a caretaker’s house, a later functioning corncrib, and…well, it comes as no surprise that by the end of the 20th century the expansive estate had been sitting on the market for several years.

Wine Country, Italian Style

In the Heart of Napa Valley, a Contemporary Farmhouse Settles In

Constructing a residence from scratch that feels as if it has always been there is an exacting art. Its success depends on a seemingly endless array of details—the use of fieldstone that might have been dug from local earth, for instance, or the anchoring presence of gnarled trees with languorous branches that look as though they have survived a hundred summers.

Presented with a rare tabula rasa in coveted St. Helena in California’s Napa Valley—the surrounding vineyards destined to become Duckhorn merlot—designers Jacques Saint Dizier and Richard Westbrook, of Saint Dizier Design, and architects Hugh Huddleson and Karen Jensen Roberts set about creating what Saint Dizier calls an “anti-villa,” a farmhouse-inspired hamlet at the end of a quiet road for a peripatetic couple and their visiting family.

“We thought of the residence as if it had an agricultural purpose,” says Saint Dizier, who is based on the other side of the mountains, in Healdsburg in Sonoma County. “We wanted to bring in the vines, make the house a believable part of the vineyards.”

The Architectural Digest Greenroom

Creating a Stylish Throwback to the 1970s Backstage at the 81st Annual Academy Awards®

Stephen Shadley is no stranger to big Hollywood productions—or to what it takes to pull one off. “When I started out, I worked as a scenic artist at 20th Century Fox,” says the native Angeleno turned New Yorker. “In those days backdrops used to be hand-painted.” Later he turned to interior design, and he has counted an array of stars among his clients. For the Architectural Digest Greenroom at the 81st Annual Academy Awards, Shadley was able to draw on his extensive Tinseltown experience, creating an oasis reminiscent of a chic 1970s pad atop the Hollywood Hills—one that was “quiet and contemplative, with a soft palette so no matter what someone was wearing, it would look good,” he explains.

The centerpiece of the space tucked just off stage at the Kodak Theatre was a photographic backdrop of the city taken from Mulholland Drive. In a fitting turn of events, the image came from the scene shop where he first worked. The backdrop gave the greenroom’s famous visitors “a sense of being outside for a moment,” he remarks. “They could look at the sky and gather their thoughts.”

Shadley employed a few other tools from his Hollywood bag of tricks to make it feel a little bit more like home. “I had just finished a project that had massive stone walls and huge expanses of glass,” he reports. The designer was so happy with the results, “I had a scene shop replicate the stone. When you looked at it, you had the sense that they were real,” he says.

Theory of Relativity

Soaring Volumes in the Country Allow a Family to Reach Out and Connect

Sometimes it takes a building to explain the obvious. Having completed a weekend house in southwestern Michigan, a Chicago couple with three children, two to eight, recently discovered one of the primary laws of space and human nature: Kids expand into the space allowed. “In our place in Chicago, we’re kind of on top of each other,” observes their mother. But in the country, the kids expatiate into the 7,800-square-foot house and 30 acres of surrounding farmland. “When we arrive, they run around the lawn, then they do laps inside the house, in the great room and in the circuit from the master bedroom to the other end of the house. After a while, they hang out with their toys in the basement, and then it’s up into the bedrooms.”

For urban kids, space is freedom, a call to joy in a much larger sandbox.

When the couple commissioned Chicago architect Margaret McCurry to design their getaway, the bottom line was to create a trampoline for the kind of family life that now seems extinct in America—the all-in-the-family lifestyle that once teemed on 1950s television. The boys would bunk together in the same room (fitted with shiplike beds) and, between pillow fights, learn how to share their common bathroom. The cousins would visit during Huckleberry Finn, gone-fishin’ summers, and they’d all spend weeks together in an informal family camp cornering grasshoppers in the cornfields. They’d pick berries in the summer and apples and pumpkins in the fall. The husband, an entrepreneur and publisher, comes from a big midwestern Catholic family, and he wanted a house that would bring, and keep, the immediate and expanded family together. There’d be a pool: Families that swim together, get together.

[DFR::26712-1154-ls|align_left_1]